Dialogue That Doesn’t Suck Part I

The Five Deadly Sins of Dialogue You Should Avoid Like the Plague

Writing poor dialogue is like waking someone up during REM sleep. Everything seems great until suddenly you hear a foreign sound that’s different from the world around you and like that, you’re zapped out of the dream and brought back to reality. That’s what it’s like to experience bad dialogue in a movie. It’s not cool.

You gotta get dialogue right because that keeps your audience in the story and it’s what they’re most sensitive to. It’s basically the centerpiece of your screenplay. You can make a mistake here and there with your action lines and formatting, but if you mess up dialogue sequences in the first few pages, no one will likely read beyond that. Some producers have even admitted that they don’t examine the action lines when reading a script to decide if it’s good. They just read the dialogue. So yeah...Don’t mess this up.

No need to panic, though, because it’s not that challenging once you get the hang of it. It’s just hard learning how to do it. Okay, yeah, no. Who am I kidding? It's really hard, even after learning how to do it. So, perhaps some of these tips will prove helpful. Unfortunately, there isn’t a specific formula for writing good dialogue.

No, the only real way to write good dialogue beyond developing your sense of creativity is to practice often and to be mindful of these considerations when choosing your words. There’s quite a bit to consider, so I broke this into two parts. This first part will cover things you should consider avoiding when writing dialogue and the second part will cover what you should consider doing.

Why Do We Write Dialogue?

Before we dive into the subject, I think it’s important to ponder for a moment on this seemingly straightforward question that not many people even stop to think about. Why is dialogue incorporated into stories? The obvious answer is that we have characters. Characters generally speak to convey information to the audience and move the story. But that’s not the only reason. We also create dialogue because we want our stories to move in a compelling way that feels real and using good dialogue is perhaps the best way to achieve this.

So the fundamental key to dialogue is authenticity and whether your characters express that in the words you’ve come up with inside the reality you designed. That’s why writing dialogue is so hard. The story is one reality and the one you’re in is completely different.

Mentally, you have to step out of your shoes and into the shoes of not just the main character, but all the characters. That’s hard to do, but it’s honestly what you have to do if you want to create good dialogue because that’s what it’s all about for your audience; whether or not you can suck them into the invented world. And if you can’t step into the shoes of your characters, then how do you expect your audience to do it? Just something to think about. Alright, then. Let’s get into the weeds, shall we?

The Five Deadly Sins of Dialogue

There are many things you shouldn’t do when writing dialogue, but these five things are the most common mistakes made, which can ruin an entire story if there are enough of these in your script. Avoid these to significantly enhance your dialogue so that at the very least, it’ll sound authentic and natural enough to pass.

On the Nose Dialogue: This is when your dialogue states what everyone already knows, whether it’s something obvious to the audience or the characters or both.

Example: “Luke, we’re in danger because Darth Vador is here and he’s trying to kill us.”

Basically, don’t do that. It sounds super fake and no one would ever say that in this context because the audience knows that Luke and the others are in trouble and so do the characters. Inevitably, that will ruin the sense of authenticity and realness.

On-the-nose dialogue also communicates exactly what the characters are thinking without subtlety, implied language, or subtext. Subtext is either an expression or dialogue that’s uttered, which reveals a deeper meaning, generally something that relates to the central message and moral argument.

A simple example would be saying that you’re fine when you’re clearly not fine. In the absence of subtext, you would express that you’re not all right and then go on to explain why you’re not. With subtext, you might use certain expressions or ways of saying things that convey different messages to tell a deeper story.

Sometimes having the characters just come out with it is good, so you don’t need subtext in every line. But sometimes you want to express something deeper without saying it outright because it would feel too unnatural if it was. This is where subtext comes in handy. It’s using dialogue and action that, on the surface, says one thing, but conveys something else that’s deeper and more hidden within the character. And if you don’t have subtext in the areas that would make it feel more natural, then you’re likely creating on-the-nose dialogue. So, stop doing that!

Exposition Dumps: This is something novice writers are infamous for. It’s when characters go on long-winded rants that are way too long to feel natural. Think about when you have a conversation with someone. Do you spend five minutes taking turns going on long diatribes? No. People tend to use short and choppy sentences that often aren’t complete because we pause in thought or we’re interrupted by the other person. So when you add too much exposition in your dialogue, once again, you ruin the authenticity of your story.

The most infamous use of bad exposition is using a character to make a major philosophical point about the entire story. I’m guilty of this, even today, and it never fails to make me cringe when I realize it.

Look, I get it. You want to make sure you get your point across to the audience. The thing is, scripts ideally turn into films. Films are visual, so you can utilize action and environment to convey many things without expressing them in dialogue. And, oftentimes, using action and environment is obvious enough because the audience isn’t stupid. And don’t you ever believe that because if you hand-hold them with on-the-nose dialogue and exposition dumps, you’ll definitely write poor dialogue.

Now, granted you may have a character give a speech that’s inevitably long, or maybe you have a character going over this elaborate game plan. That’s okay if it’s no longer than it has to be and is relevant to the story’s progression. But when you create these dialogue moments, at least break them up with action so that we get more than just some person on a podium talking for a minute. That’s a good way to keep people engaged, especially if what is being said juxtaposes what is shown in the action. This doesn’t mean all of these situations need a juxtaposition, but it can certainly help if it’s right for the moment.

Wordiness: So maybe you managed to avoid the exposition dumps. But did you avoid the little parts in your dialogue that add extra words?

Here’s an example of what I mean:

Example: “Dale, you and your friend can not do all of that in one hour.”

Unless your character is C3PO, this will sound weird when an actor says these lines because people are messier when they speak. So instead of having all those words get rid of them. This way your actor can say the lines more naturally, such as, “You can’t do that in an hour.” It sounds easier for the actor and more real for the audience. Also, it makes sense given the context because both characters know that Dale has a friend who is helping him, which means he doesn’t have to say, “...You and your friend.”

A good technique for avoiding wordiness is to read your dialogue out loud. In fact, get out of your chair and act the part. It’s goofy and will make you feel like you’re going crazy, but doing this can really help you chop the fat because when you utter the words it becomes easier to recognize the parts that make it too clunky and inauthentic.

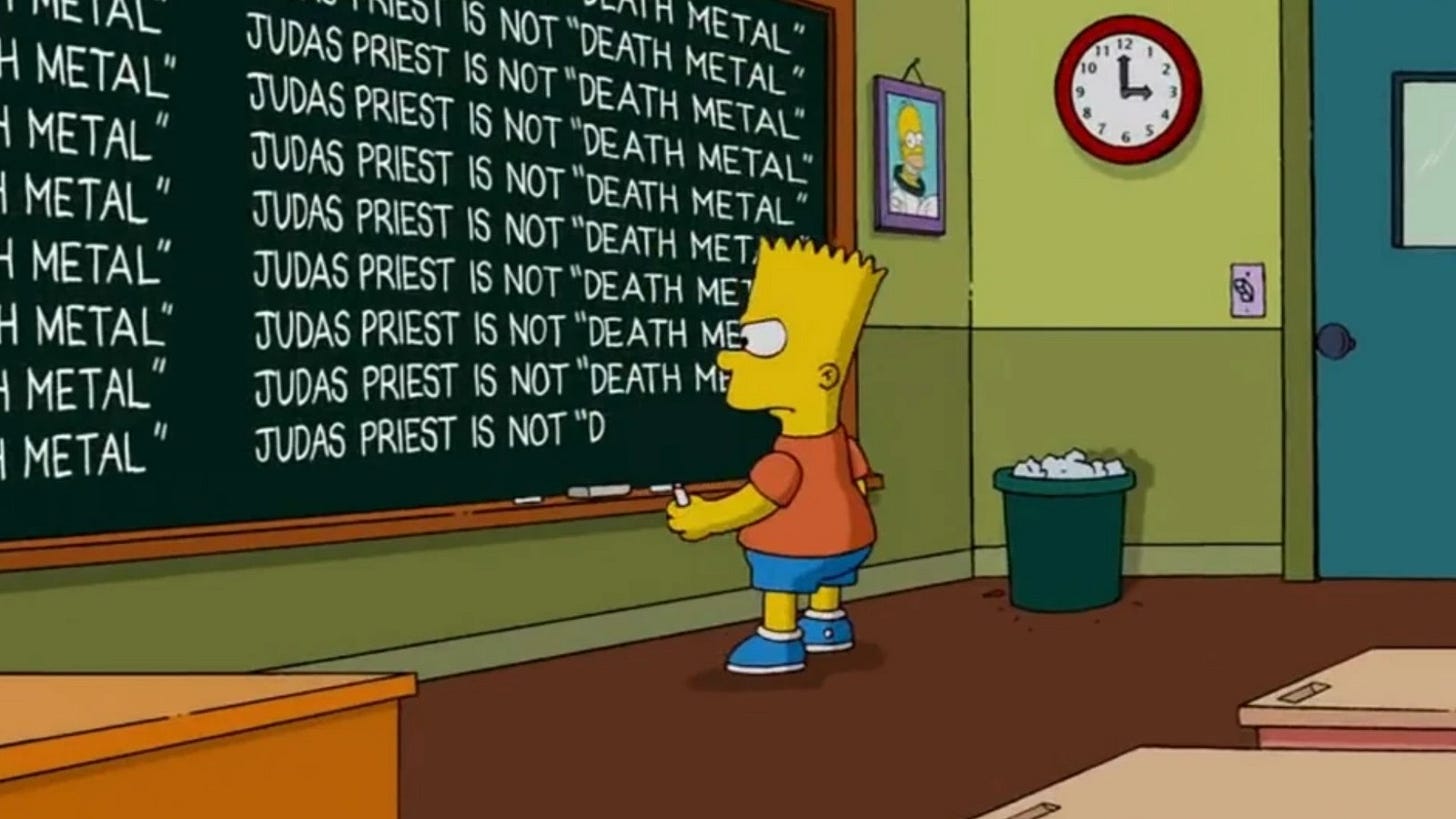

Repeated Information: Repeated information is another big no-no, like how I just wrote repeated information in the first line of this sentence, even though the section is labeled, “repeated information”. I didn’t have to write that twice, and it’s the same when writing dialogue. If an action or something else expresses a point, don’t add it to the dialogue.

If your character says something and a few lines down you rephrase that same thing, that’s still repeated information. I do this all the time because I like writing things and sometimes I develop a better way to phrase it later down the page. When that happens, get rid of one of them because when you repeat information, you get the audience to roll their eyes and that sucks. So express it once and only once. Remember. The audience isn’t stupid!

Dialogue Without Purpose: The final big no-no is perhaps the most important to consider. Never, ever, ever write any bit of dialogue that doesn’t have a purpose to it. What do I mean by that? Well, think about it. Your story ideally will have a central message or a point to it, right? So if your entire story has a point to it, then every scene has a point to it, and if every scene has a point to it, then every character has a point to them, including what they do and say.

If your character in an action movie starts with friendly banter about how much they love ice cream and you take up a page of dialogue? Well, that doesn’t necessarily mean there isn’t a point to it. Perhaps you’re trying to convey the two character’s relationship to each other like what Quintin Tarantino did in, Pulp Fiction with Jules and Vern during the “Royale With Cheese” scene.

That was kinda long by traditional standards, but it worked well because it was interesting banter that showed us they were good friends and quite possibly co-workers, though, in the beginning, we weren’t sure what they did for a living. And it was more engaging because, not only did the banter segway nicely into meaningful dialogue that set up the plot and exposed us to the idea that these guys may be bad, but while all of this dialogue exchange was happening, we also saw the characters park, get out of their cars, walk up some stairs, and knock on a door. They didn’t just sit in the car and talk the whole time. There was a progression, both in action and dialogue.

So there was meaning in that exchange and a sense of escalation or a sense that we were being led to something interesting, even though it was seemingly insignificant banter while two guys drove, parked, and walked. That’s why significance and intent matter in dialogue whether it’s a pivotal scene or something that seems insignificant. If there isn’t a purpose in the dialogue, then the scene will fall flat no matter how exciting or mundane you make it.

Conclusion

So those are the big five. There are certainly more than just five things to avoid when writing dialogue but these are the most common ones you really wanna pay attention to. The best way to avoid them, beyond being aware of these mistakes is to strive for authenticity. Always ask yourself, “Does this sound natural for the World I created, and does it have meaning that relates to the story and central message?” If you can’t answer these, then, perhaps, before delving into the script, you should focus on laying out that strong foundation for your story and characters, first, so you know how to land your story on page.

That’s part of the reason my brother and I developed Story Prism. With this, you can develop a strong foundation before you get into the weeds. Think of it as a North Star when you get stuck on some of the choices you have to make with your character’s dialogue.

If you can nail a meaningful foundation for your story and characters before you write you can much more easily create better dialogue choices from the start and, hopefully, avoid some of the common mistakes mentioned above. So that does it for, “Part I of Dialogue That Doesn’t Suck”. Next time, I’ll dive into some things you should consider when creating dialogue. Until then, best of luck in your writing endeavors!

__________________________________________

Story Prism,