Climbing the Creative Mountain on a Shoe-String Budget Part II

How to Plan Out Your Film, Find Your Locations, and Nail Down the Right Actors for Your Movie

WARNING: This post is long but full of valuable information that will help you make your first film. Hope you enjoy it!

_____________________________________

Welcome back! This is part two of a three-part series where I dive deep into getting started as a first-time filmmaker when you have no money, zero connections, or any skills. In the last post, I discussed the strategy of befriending local filmmakers to help you make your film as well as the fundamental importance of ensuring that your script is ready and budget-friendly before shooting.

Now, I want to get into the nuts and bolts of planning out your film. There are three phases you typically go through when making a film and that’s pre-production, production, and post-production. As you go through each phase the story changes and is re-told differently. So never be married to the original script. The more you fight the changes, the worse your film will be. Okay, so let’s get into it.

Plan It Well

There’s something to be said about spontaneity in the filmmaking process. Some of the most iconic moments in cinema happened completely unplanned, such as the improvised scene in Goodfellas. So I’m a huge fan of changing things up when you’re in the moment and just rolling with it.

But that’s really hard to pull off when you’re running behind schedule, you’re missing crucial shots, and your DP (director of photography) had to bail after lunch. Oh, and everyone on set is pissed because you didn’t bring enough food and now they’re ready to walk out.

Spontaneous movie magic happens when you plan everything right. Without a well-planned film, you’ll be way too stressed to think about doing something better. Plus, you won’t be able to concentrate on what’s most important, which are your shots and the actor’s performances.

Your film will suck and worse, you’ll set a bad precedent for yourself, and others will be reluctant to help you out again. Look, no one’s expecting you to write a masterpiece. That’s insanely hard. But what isn’t too hard and something you can manage the first time around is planning your production well so that everything runs smoothly.

Like everything in filmmaking, there are a million different ways to plan your movie, but for my brother and me, it always starts with a master budget list.

The Master Budget List

The very first thing we do is create a master budget list. This is what our template looks like. We basically have a list of cast, crew, locations, props, wardrobes, and extras (paper towels, chairs, production insurance, etc) as categories. The idea is to comb through your script and generate a list of everything you need based on these categories so you know what you need and how much your production will cost.

Now, if you notice along the top of the columns there’s a category for cost per day, the total cost for production, the cost for pick-up day, and a link to the item. The cost per day is just the cost of using that item for one day. A lot of your stuff will be fixed costs as in, you buy it once and that’s it. But some of your items might be rentals like a specific prop or location, so those are variable costs that need to be factored in if you’re shooting multiple days.

The total cost for production is just the total cost of using that item for the duration of that production. So if you’re shooting two days and your location is 50 dollars a day, the total cost would be 100 dollars. Pretty self-explanatory, but important nonetheless. The cost for pickup day is the cost of all your items and people used on an extra day that might be needed to finish the shoot.

Typically when planning for a day, you also want to plan for an extra day just in case you’re unable to get all the shots. The total in this column tells you how much that pick-up day will cost. Finally, the link to the item is exactly that. It’s a hyperlink to the site where you can rent or purchase that item. It’s good for keeping a record of your purchases, and it allows you to figure out your total cost before you buy the things.

So that’s a budget sheet. It’s super easy and provides a list of all the items you need to rent or purchase. Also, keep in mind, you can return anything you didn’t use or only used once. Doing this is cheap, I know, but if you’re pinching pennies, it’s an excellent way to recoup some of your expenses. So hang on to your receipts!

Pre-Visualizing Your Shots

Once we have our master list, we then get into pre-visualization. This is just a technical way of saying, “Visualize your story”, and we do this before production so we know what to shoot. The name of the game is time. You want to capture everything in the shortest timeframe possible because you’re working on a budget, and with every minute on set, that’s money being spent.

New filmmakers will shoot to the edit, meaning they’ll come up with a list of shots based on how they see the edit in their heads and then capture all of them in order. That’s a huge mistake because not only will that make it harder to edit, but logistically, it will take forever to shoot. Even shifting the camera a few feet can take several minutes, sometimes even 30 minutes or longer to set up.

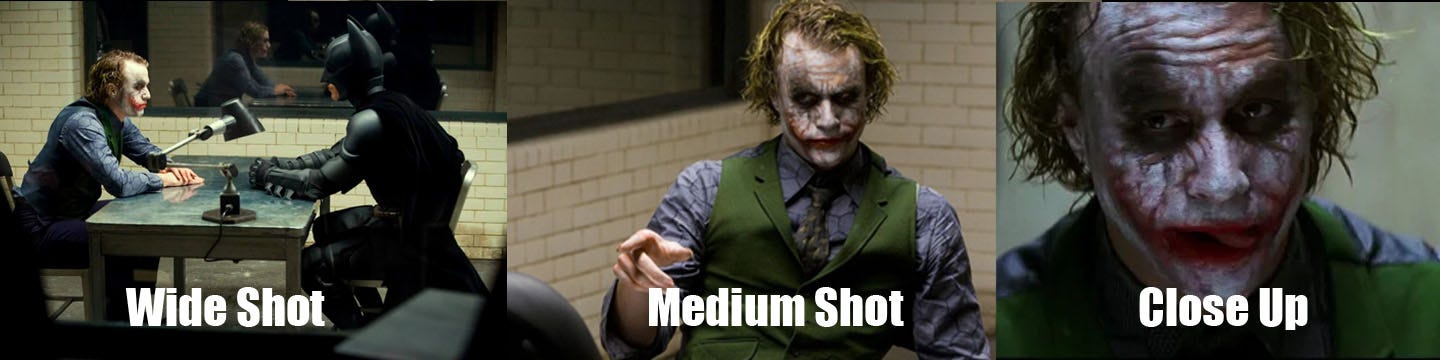

So shooting to the edit isn’t practical. Instead, you want to block your shots out based on where the action takes place and where it goes. Let's say you have a scene with two characters sitting in a room talking before getting up and fighting, like the Joker interrogation scene in, “The Dark Knight”.

In this scenario, we can break it up into two blocks. The first block, which we’ll call 1 is capturing everything when they’re sitting down and talking. The second block, which we’ll call 2 is capturing everything that happens when they’re standing up.

In each block of shots, we need a master shot, which is typically a wide shot that captures the entire space. Following that, we also need to capture our medium shots and close-ups of each actor.

And with each of these angles, we name them by letters. So our master shot in the first block would be labeled 1A. The medium and close-up shots would be labeled 1B, 1C, and so on. The number indicates the block and the letter indicates the shot within that block.

If the scene calls for it, we may also need to add in some extreme close-ups of either the actors or something in the space. But you should only do this if it means something to the story such as establishing the location, emphasizing an object, or showing an expression on someone’s face.

Now remember, every shift you make with the camera adds time, so the most time-efficient way to capture your shots is to get the entire first block on a wide. Then, move into your medium and close-ups and capture the entire first block again with each actor. Record each shot all the way up to the point where the characters are standing up. Then, you just do the same thing for your second block when they’re standing up. Capture everything on the wide, move into the mediums, and finish with the close-ups.

And by capturing everything, I mean that you want your actors to go through all their lines and action within that first block, in that one shot. Then, you switch it up to the next shot and have each one act everything out, again, within that same block. This is called coverage and will make a lot of sense when you edit because you’ll have a lot of wiggle room to modify things like pacing, just in case what you envisioned didn’t turn out well on camera, which is often the case.

But how do you do all of this when you don’t have any cast or locations to reference from? Pre-visualization is an ongoing process, which will evolve as you plan your film. So ideally, my brother and I like to do an initial pre-vis before we find our locations and actors. Then, as we secure these things and do rehearsals, we modify our shots accordingly.

This is so we can come into casting and location scouting with ideas already in our heads. The way we initially previsualize is by sitting in a room and physically acting out each scene. And while doing this, we use CineTracer to create simple 3d models of the set and the shots we want to capture. This allows us to turn our vision into a storyboard that we can show our crew and have around as a reference. Here’s an example of a storyboard we created for our most recent film. And here’s how it came out (Warning: NSFW!)

It’s not exactly one-to-one, but it’s pretty close. Having this allowed us to capture a lot of shots and actually get everyone out on time. Moreso, it made the planning smoother because now, we knew what we were looking for.

So that’s the basics of pre-visualization. Obviously, you can design much more complicated shots, especially if the scene calls for it, but if you’re just starting out, then I would try to keep it simple. Or, don’t. Either way, you’ll learn something just by trying!

Locations

While previsualizing, you also want to search for your locations. Perhaps you already have a space in mind, but what if you don’t? Well…Looks like you gotta scout.

First, take the list of locations from your master list and Google them to find the spots. Need a cruddy motel? You can find that on Google. Need a nice park with a playground? Google, baby. What about a cozy diner? Well, that one’s better to find on Ask Jeeves. No, just kidding. It’s Google.

Unfortunately, though, a simple search won’t solve all of your location issues. Sometimes you need to find something like a specific-looking alley or the roof of a parking garage. For these, use Google Earth. Just hover over your general area and start searching.

Now, maybe you need an uncommon location like an off-road trail with an overlook and Google Earth isn’t cutting it. If you want to dig deeper, get on forums with off-road trail enthusiasts and search for places near you. It takes time, but you can find a lot more in these niche spots. And they have them for everything like abandoned buildings, underground tunnels, old rail lines, etc.

Then, there’s Airbnb. A lot of homeowners aren’t open to the idea of filming at their houses. But some are, and you’d be surprised by what you can find for a pretty affordable rate. Just make sure you let them know your intentions because the last thing you want is for their neighbors to call them because they think you’re filming a porno!

Of course, I can’t forget to mention your local film office if you live in the United States. Every State has one and they’re designed to help you make your film. Check out their website and see if they have a database of locations that have already been scouted.

As you find locations, make a list of 5 or 6 places for each spot you need. Once you have your list of possible options, then it’s just a matter of visiting them. If it’s owned by someone, consider giving them a call in advance to see if they’re even open to the idea. No sense in traveling all that way out there just to be told you can’t film.

When you get to the locations, take a lot of pictures of the space and where you want to shoot. You can even capture some footage with your phone and act out certain parts. This is important to do because you’ll want to show them to your DP and have them around for yourself as you revise your shot list.

Also when you’re at the locations, you’ll want to consider logistical issues such as parking, constant noises from nearby places, lighting that can’t be turned off, a space to store gear, having a base camp that’s away from the shooting location, as well as easy access to power for setting up your lights. Any one of these things can be a huge hindrance to your operation, so just be mindful of them.

Another thing to keep in mind is private versus government-owned locations. Government-owned locations may be free depending on the State and the location, but they all come with stipulations such as production insurance, which can be very costly depending on your budget. Also, if you’re planning on using things like prop guns, you’ll need to pay for a cop to be there. And things like fire? You bet your ass they’re going to require a certified specialist to be in your crew, which you’ll probably want anyway because it’s fire.

Privately owned locations are much easier to secure, cheaply. It just depends on who owns it and how big the place is. If you’re talking about shooting a film at a mall or at the Mets Stadium, it’s possible, but you’ll have to either fork out a ton of money or have some nice connections. Even then, you’re guaranteed to be limited in when and where you can shoot.

If it’s a smaller more mom-and-pop place, there’s a good chance you can get the location for free or for a cheap rate and without all those stipulations. Most private places don’t get hit up by random filmmakers, so generally, they’ll be pretty excited about it.

Once you’ve driven all over town and looked at multiple spots, review your pictures and video before making a decision. When you do, call the owners, let them know you want to film there, and tell them you’ll get back with a shooting date and a location release form. That form is super important because without it, you could shoot your film and for whatever reason, the owner could legally require you to cut their location out of your movie. And if the location is in a bunch of crucial shots, you’re shit out of luck. So always, always, always, make sure you have the owners sign a location release form.

Finding Your Cast

The last thing I’ll talk about before wrapping up part II is finding your cast. We do this by hosting casting calls. Unfortunately, you’re probably not going to find a Dicaprio or Meryl Streep. But some will be pretty decent and a few will be really great. The great ones, of course, will likely be more expensive. Not outrageously pricey, but definitely not sixty bucks a day.

To get started, you need to find a place to hold casting calls. Zoom is okay, but it’s not the same as doing it in person, so try to avoid online meetings. If you have a house with a large space, DO NOT hold casting calls there because you’re exposing your personal address for everyone to see and it screams unprofessional.

Actors are looking for opportunities and know that they probably won’t find them from a director hosting casting calls in their living room. So find a quiet place that’s spacious and uncluttered like meeting rooms you can rent out or an office you can use over the weekend.

While securing the spot, create an advertisement like this so you can blast it out to all the right channels in your local area. Make sure to include an introduction of yourself and what you’re doing, a synopsis of your story, a brief description of each character you’re looking to cast, and your contact information. Also, if you mention payment, you’ll get a lot more responses. You don’t have to specify a number just yet, but it’s a good idea to mention it because money talks.

Once you’ve made your ad, blast it out to as many actors as possible. Find universities nearby and reach out to their theater departments. Search for local theater and acting groups, run a Facebook or Craigslist ad, reach out to your local film office, find improv or comedy groups, etc. There are a lot of different options, you just need to find them.

Distribute the ad and see who responds. Typically, actors will send you their resume, headshots, and a demo reel. Resumes are irrelevant unless they’ve done work on well-known shows or movies. That can, at least, tell you if they’re decent and professional. Beyond that, it doesn’t really matter what school they went to or any other work they’ve done.

The headshots are nice because you can see what they look like, which is important. But what’s most important is how well they can act. Just because they look the part does not mean they can act the part, which is why having a demo reel to see their performance is the most important thing to have when evaluating the actors.

Hopefully, you’ll get a lot of responses from your ad, but I would expect no more than 15 to 30 people. Regardless, you’ll want to comb through their documents and find the most promising ones. Get back to those actors and send a thoughtful rejection letter to the ones you didn’t choose. Your follow-up email for the ones you selected should include a warm introduction congratulating them, the actor sides, the script, and a range of dates to choose from that work for you.

Actor sides are just one to three-page snippets of your script that you have your actors read. Typically, you want to find a range of moments that capture what they need to perform. So you may want to pick moments when they’re really sad, happy, or angry. Give them those pivotal scenes so you can properly evaluate their performance on the day.

When having them choose a date, use Calandy and send a range of options. Then, make a simple excel sheet like this so you can mark them down for the times they choose. This will be helpful to have because now you’ll know who's coming in and when, so you can scratch them off if you don’t like their performance or put a star by their name if you want them for callbacks. After they choose their dates, send a follow-up email confirming the time, date, and place.

There is one thing to note about the time slots. You want to give yourself enough time with the actors to determine if they’re the right fit. 5 minutes is too short. 15 to 30 minutes is much better. This doesn’t mean you’re going to use up the entire time. It just means you’ll have that time to experiment with the actors. As soon as you’re convinced one way or the other, feel free to thank them and let them know you’ll stay in touch.

Come prepared for the auditions. Make several copies of the sides because they have a way of disappearing. Also, be sure to have your excel timesheet and a place on there to write notes. Bring a case of bottled water, too, not just for yourself but also for the actors. And find something to pass the time because you may have 15 actors who are supposed to come out, but only 6 show up. Also, if the casting room has a lot of twists and turns to get to, create some signs with arrows, and make sure you have your phone off silent just in case they call.

Finally and most importantly, bring a camera, a tripod, and ideally, a friend to help you film each actor. Set it up on a medium shot and make sure to hit record when they start acting! These video auditions are crucial to review before making your decision.

After a quick introduction, hit record and have each actor state their name and the role they’re trying out for. Then have them go through it without any direction so you can, first, get a sense of how they interpret the character and the scene on their own. A great actor will be pretty close to nailing it on the first try and may even nail it perfectly or totally reinvent the character. A bad actor will be wildly off and sound fake. An okay actor will be off, but maybe not completely and will at least sound natural, which is something you can work with.

However, this is all contingent upon how well-written the dialogue is. I’ve seen really good actors do horrible auditions because the dialogue was poorly written. So make sure your dialogue is good, otherwise, it’ll be much harder to evaluate them.

Once you get a sense of how well they can act without direction, you then want to see how well they can act with direction. This time, have the actors do it again, only tell them exactly how you want it. But when you give direction, it’s imperative that you don’t muddle it up with the details.

They don’t need to know the whole backstory. Just tell them what is happening to the character at the moment and use common analogies to express how you want them to feel, such as, “Imagine how you felt when your boyfriend dumped you.” but really dig into how something like that might have felt. Remind the actors of things they actually experienced to help them tap into how the character should feel. Do this, and you’ll get a sense of how well they take direction. But don’t forget to test them on facial expressions.

Oftentimes, as filmmakers we like to convey the message without words, and that can mean holding the camera on your actor’s face as they begin to express an emotion without saying anything. So you really want to make sure they can give the right kind of expressions, otherwise, you might have problems on the day of the shoot.

You also want to get a sense of their emotional range, so have the actors redo the lines with different emotions. If it’s a sad moment have them go from kind of sad to really sad. If it’s a happy moment, have them go from kind of happy to completely ecstatic. And throw a curve ball. Maybe it’s a moment when the character is mourning the death of a loved one. Have them do it gleefully or angrily.

So get a baseline on their abilities, a sense of how well they take direction, and a taste of how good their facial expressions are as well as their emotional range. That’s really how you evaluate an actor for your film. And before they leave, always make sure you ask about their availability for the next several months. Also, if your film has specific requirements such as partial nudity or swimming in the middle of a lake, make sure you ask if they’re comfortable doing them.

Those are your auditions, and it’s likely that you’ll be doing these over several weekends because, again, it’s hard to get hundreds of actors out for casting. You’ll probably be doing 6 to 10 at a time. Once you’ve figured out the top three or four actors for each role, call them back and schedule another audition, only this time you want to see how well they work with each other. Match them up with your other cast members and see what works. The chemistry between actors is crucial if you want them to riff off each other, effectively.

After your call-back, take the time to evaluate your choices. When you picked the right ones, send them an email letting them know they got the part and that you will get back to them with a specific date. If you can, try to give them a relative date range, at least. And, of course, for the actors you didn’t choose, send them a kind rejection letter.

You may also want to start talking about compensation in this email if you plan on paying them. Don’t quote me on this, but I believe the standard rate for a union (SAG) actor is $125/day for low-budget films. If they’re non-union then none of this is an issue…except for the fact that you know, they’re human beings who should get paid for their work.

The unwritten rule of compensation on indie no-budget films is that you either pay people with money or sweat. So unless you helped this actor out on a bunch of their films, you should really consider paying them the standard SAG rate, especially if they’re your lead. For actors with a few lines who show up in a scene or two, you can probably get away with 60-80 bucks. But definitely, at least pay your main ensemble because they work really hard, and giving them your shitty first film for their demo reel isn’t fair compensation.

Conclusion

Wow, that was a lot. I really apologize, but unfortunately there’s a lot to cover. So there you have it. Pre-visualization, location-scouting, and casting calls.

These three things are fundamentally important to nail down if you want a good production. That’s why it’s okay to take your time at this stage since you haven’t set a date. Obviously, you don’t want to spend a year deciding, but take 2 or 3 months to plan it all out. Re-work your previsualized shots, search high and low for the right locations, and hold multiple casting calls until you find the right actors. Don’t just settle on the first choice.

Okay, that’s it for now. In part III I’ll cover the rest, which will include securing crew, dates, tech scouting, rehearsals, last-two weeks, production, and editing. Sounds like a lot, but these are actually fairly straightforward, so don’t fret. We’ll get through this! Until then, best of luck in your writing endeavors!

Story Prism, LLC

__________________________________________

A very helpful article. I really appreciate the details you get into.